|

When I say “core”, what comes to your mind? I'll give you some time to think...

Most people think of "abs" - an image of a fitness model flaunting a shredded midsection - rectus abdominis, if you want to be textbook - on a magazine cover.

0 Comments

When I don't have access to the gym, I do all my strength training from home.

If you don't have access to a gym either, or maybe you are still not feeling like getting into one, you can becomes stronger, develop muscle and reduce pains and aches by doing the strength training from the comfort of your home. So, what equipment do you need for this? Yes, this again. I know keep talking about creating and maintaining healthy habits so we can achieve our goal of becoming stronger and healthier in general, and get to age like a fine wine.

So I thought we could dive into what are habits and how we can build them, as well as some strategies we can use to make sure we keep them. The why

As I’ve written before on other blog and social media posts, strength training can bring great benefits to our overall health, such as:

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least 2 sessions of strength-promoting exercise throughout the week. And, fortunately, this recommendation has been added to the physical activity guidelines of most countries around the world. Brief comment before we begin: I will get technical in this section and probably at other points in this article. But I promise it is worth it. Strength-promoting exercise, which I will call strength training from now on, independent of whether it is done at a gym lifting weights or using any bodyweight training like calisthenics or gymnastics, has been shown to have a well-established association with reductions in all-cause, cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and cancer-related mortality and contributing to living longer. In a study that analyzed data from The Health Survey for England and the Scottish Health Survey it was found that among those who perform strength training twice a week, there was a 23% less risk of death during the length of the study (data was taken from surveys starting in 1994 and participants were followed until 2011) When we specifically think of muscle tissue (or muscle mass) and muscle strength, we need to consider how these two change as we age and how important it is we keep both. Another study by researchers at the University of Indiana has proven that the most important factor in living a longer, healthier life and reducing the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease is having greater muscle strength. We may think that more muscle mass equals more strength, but this is not always the case. Of course, the percentage of muscle mass will differ from person to person based on their training, including type, frequency, and intensity, and their lifestyle, as well. Sedentary periods in each person’s day and non-training specific activity (leisure physical activity) are also correlated to muscle mass and function (strength), and it has been shown that in less-active adults, replacing one hour of sedentary time with “activity of light or moderate-to-vigorous intensity was significantly associated with 18% and 42% lower mortality, respectively” We’ve heard before the term “sarcopenia” (Clark and Manini) This is the term used to describe the age-related reduction of muscle mass. And now, we can introduce as well the term “dynapenia”, used to describe the age-related loss of muscle strength (Dynapenia (pronounced dahy-nuh-pē-nē-a, Greek translation for poverty of strength, power, or force) is the age-associated loss of muscle strength that is not caused by neurologic or muscular diseases) Findings from the Indiana University study, show that muscle strength is an important component in defining sarcopenia, as the loss of muscle mass alone does not fully reflect the loss of muscle function. It is the combination of loss of muscle mass and loss of muscle strength that creates these debilitating conditions in older adults and can be life-threatening. All in all, maintaining muscle mass as we age is crucial to help us withstand disease. Working on muscle strength together with the maintenance of muscle mass is critical as we age to improve quality of life, extend it and reduce the risk of all-cause mortality. The What

As I briefly mentioned above, and you will see more on this below, we can choose from lifting weights and pumping iron at the gym (or at home!) or doing a form of bodyweight strength training. When it comes to body weight, some examples of activities that can help us develop muscle mass and strength are calisthenics, rock climbing (indoors or outdoors), gymnastics, and aerial sports, such as pole fitness, silks, and aerial hoop. In this article, I will focus on strength training with weights. However, the principles I will describe here can be applied to bodyweight training as well. The only difference will be the equipment used. In the coming sections, we will discuss what equipment we can use, how and when to progress, repetitions, sets and frequency of training, as well as rest and recovery times and a few other nuances. Choosing equipment: Where to start?

Chances are if you’ve never been to a gym before, you can get easily overwhelmed by the amount of equipment to choose from.

You’ll most likely find equipment like resistance machines (RMs), machines with cables and pulleys and free weights (dumbbells, kettlebells, barbells, and plates) And of course, the cardio equipment, like treadmills, cross-trainers, and rowing machines. When it comes to strength and hypertrophy (muscle-gaining) training, the reality is that there is not a one size fits all approach. Well, pretty much with everything that relates to exercise, nutrition and health there will not be one approach that is best for everyone.

However, the RMs in any commercial gym have a very general design and they may not fit every BODY properly. If you struggle to get an exercise done in an RM or feel your body wiggling and trying to adjust all the time, it may well be because the RM is not adjusted properly, or it just has one setting.

If you look closely, most RMs will have some sort of lever you can pull at different parts of it to adjust hight or distance. For example, a leg press (pic below) machine has a lever you can pull to adjust the seat and make it as comfortable for you as possible. Unfortunately, not all machines have them, and some are fixed in a position.

Cable machines add the component of having to work on the stability of your body as you do an exercise. Cables are incredibly useful as they allow us to perform movements with more freedom and we can set up the machine and our body positioning to ensure we move in the most effective way for the group of muscles we are trying to work on. Due to how much we can adjust them and our position, they are fantastic for upper-body exercises but also for lower-body, especially glute work. One of the main issues with cable machines is that it can be hard to find stability when we need it.

Let’s say we are doing a very heavy pull down and we will need our free hand to hold onto something so we can pull with the other side without compensation, it might be tricky to find something to hold onto! Ideally, we want to use both, RMs and cable machines to extract their benefits and optimize our results. And of course, these are not the only 2 modalities you can use when it comes to weight training. From experience, if you are a beginner, I would recommend sticking to these, unless you don´t have access to them, such as when you train from home.

Once again, a combination of all the tools is a great way of making the most profit from your sessions. However, not all tools are good for everyone at any given time of their training. That’s when hiring a coach could come in handy 😉 Elements like barbells, dumbbells, and kettlebells are especially useful when we don’t have access to machines. If you are training from home, you can do most exercises with these and some resistance bands. Free weights can be fantastic to work on the stability of the joints as you work on your strength and hypertrophy. Stabilizing a movement with nothing or very little to hold you (if you do movements assisted by a bench you can find some stability there) can be a real challenge. And it is a pro as it is a con. The added element of adjustability and needing to stabilize joint movement will not allow us to lift as heavy as with a machine in most cases (let’s not include powerlifters here who train specifically for that) So, if you have the opportunity to exercise at a gym, combining these with the machines will be the best choice to cover all your needs and optimize your sessions. How much is enough?

Let’s geek into repetitions, sets, and frequency of training

When we ask ourselves or others about training, we usually wonder:

If you are already exercising, you’ve probably found yourself counting how many more times you’ve got to do a movement for the set to be over, hehe 😊 In terms of how many times a week we should be doing weight training, as mentioned in the first section of this article, the recommendation by the WHO is 2 to 3 sessions a week. This is for the general population; this is something that applies to everyone. However, if you are a powerlifter or pro athlete, your number of sessions will vary, as will the type of training you get every session. Powerlifters and people preparing for a competition can easily train 5 or 6 times a week, splitting what muscle groups they target every day to keep the volume in check. A professional pole athlete can do 3 times of gym training, so to speak, plus 3 or 4 pole sessions during the week, which are also a form of strength training. A mum busy with her job/business and kids can do 2 sessions a week and that will be enough for her and her lifestyle. See what you can fit into your life that aligns with your goals and go with that! What matters most when it comes to how much we should train is total volume.Volume equals the amount of work performed. It is how much loading we get, and how many stimulating repetitions every time we do an exercise.

So, what’s all this? With loading, I mean mechanical loading: this is the actual stimulus that drives muscle growth. Stimulating reps are all the repetitions you do that drive muscle growth. To drive muscle growth, what we know so far is that we need to get enough load (weight) and repetitions to get us close to failure. So, volume is calculated based on the number of working sets we perform throughout the week for each muscle group. And working sets are the ones that we do with a load and number of reps that take us near failure. I know, I’ve said this twice already. And it’s on purpose. Notice I say CLOSE to failure. Not to failure. Close to failure is when suddenly the speed of our movements starts to slow down, when we start feeling it, and it starts to get hard. But we can still complete that rep. And maybe a few more. But we don´t. We stop short of failure when we notice those “symptoms”. And that is considered to be the sweet spot in the most recent literature. Why short of failure and not complete failure? Let’s say you are doing a biceps curl with a 10kg dumbbell. You are doing 3 sets of 10 repetitions. Every set, when you get to number 9, you start to find it challenging to continue. But you can still do that full rep and 1 more in good form. That is close to failure. Anything within 5 reps to failure is considered a working set. That will allow us to reap the benefits of the work and also recover in time for our next session. Now, let’s say you’re doing the same exercise, the same weight and the same number of sets and reps. However, when you get to 9 or 10, you feel the weight so heavy that you cannot physically complete those reps at all. So, we must stop there. You’ll still get through the session, but it will most likely take you longer to recover for your next training of the same muscles. I went down a tangent there so back to the original question, HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH? Do as much as you can while still being able to recover and improve. We don’t want to do so little that we keep training and get nothing of it (improvements) or too much that we cannot improve due to fatigue. Just to wrap up this section, you may be wondering what is best: many reps and low weight? Or fewer reps and more weight? In terms of performing working, stimulating sets like we discussed above, there is virtually no difference. Research has shown that anything between 5 and 30 reps per set will become a stimulating set if we take it close to failure. Regarding the number of sets per muscle group per week, the general recommendation is 10 to 20 working sets. But remember, IT’S ALL RELATIVE. Not 2 people are the same. We have to consider aspects such as training history, how much stress you can take, nutrition, sleep, and what sorts of sets you are doing. Start low and work your way up. Let’s say you are heating up a cup of coffee in the microwave. You wouldn’t set a 3-minute timer right away. You’d probably start at 30 seconds, check the coffee, and add some more time if needed. The same happens with training. Set, reps, number of sessions per week. It all varies from person to person. So, again: start slow and work your way up. Prioritize good quality and technique in the movement, rather than volume, especially in the beginning. And be mindful not to increase all variables at the same time. Once you get familiar with the equipment and technique, you can start adding weight, or sets, or repetitions. We’ll learn more about this in the next section 😊 In the meantime, you can continue geeking out in this article by ASCM: The New Approach to Training Volume • Stronger by Science How do we progress?

This can a be tricky but also very simple question to answer.

We have to consider 2 main aspects:

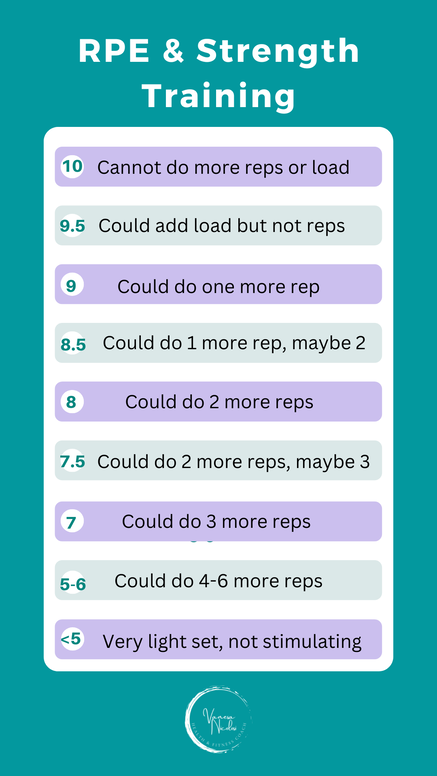

1. When we think of the when part of the equation, how do we know when we can make any changes to a workout routine to make it more effective? Surely, we will be a bit bored of doing the same workout after 3 or 4 weeks. But boredom is not the best indication that something needs to change. When it comes to strength training, unfortunately for a lot of us, repetition is key. The more reps we put on for each muscle group, the better results we will get. However, there’s a catch: remember in the previous section we discussed volume? Doing 50 push-ups a day (chapeau to those who can manage that) is a lot of reps. But not necessarily, a lot of results. If you can comfortably do 50 push-ups a day and fully recover in 24hs, then you’re certainly not working close to failure and doing enough stimulating sets. We could say that comfortably doing the number of reps and sets indicated using the current load (weight), something you used to find challenging and used to be able to take close to failure in those parameters before, is a good indicator that a change is needed. Introducing: RPE RPE is the Rate of Perceived Exertion, meaning how do you feel when doing a certain exercise? Is it challenging enough? Can you get to the last rep and feel you’re getting fatigued and close to failure? Or is it too challenging and you cannot complete the last 2 or 3 reps at all? And on the other side of the spectrum: is it so easy that you could do more than 5 repetitions in addition to what you are doing? Is it so not challenging that you don’t feel like you’re putting in any effort? Let’s make it visual, shall we? If you Google the RPE scale, you’ll find many images, most charts related to cardiovascular levels of effort. This is valid. But we got a great RPE scale (thanks to Luke Tulloch) for what each number represents in strength training. 2. Now, to answer the HOW of the progression questions. And the queen of all principles of exercise is Progressive overload: When we talk about training, we are implying there is a goal behind our sessions, ideally, we have a program to follow, and we are making notes every session to be able to see our progress. Otherwise, it is simply exercise. Mind you, exercise is very much needed, and in no way should it be undermined. You have and will continue to hear me say that movement is key to a good quality of life. And exercise of any kind is the number one hack to a longer, healthier one. However, if you have a specific goal in mind in terms of strength, hypertrophy, and endurance, then you will need a program to follow and a way to track your progress. And that is training. Training of any kind follows certain principles, like that of specificity, meaning it has to be specific to the individual and their goals; or reversibility, which means pretty much “use it or lose it” (if you stop training, the progress you made can be reversed) When it comes to progress and adapting a program, the key, however, is the principle of progressive overload- Overload refers to:

In order to progress, we will put our bodies under stress with training, and this stress or overload can be achieved by playing with any of those variables. We call it progressive overload because we cannot modify all the variables at one given point of the program and expect good things to happen. If we tweak it all, we will end up failing at the exercises and not progressing. Instead, we will want to increase the stress or load gradually as we progress in our training. The increase can be achieved by adding more weight, changing the tempo of an exercise (for instance instead of going down to a squat at the usual speed, we can go down in 1,2,3 hold 1 second down, and then come up) or adding more sets or reps, for example. So, let’s say at the start of your program (week 1-day 1) you are doing 10 split squats with no added weight and that feels like an 8 or 8.5 on our RPE scale. By week 4, you do your set of split squats and realize these 10 reps are feeling more like a 7 on the RPE scale. In other words, it feels easier to do this exercise in this manner. The following week, we will want to switch up this exercise a bit to make it more challenging for you again and get you back on your 8 or so of RPE. Here’s is when progressive overload comes into play. How can you make this exercise more challenging?

But you cannot make all these changes at once. For the exercise to continue being effective, you’ll want to change just one thing. Choose one and stick to that for a couple of weeks. When it gets easy again, you can make another change in any one of the variables mentioned before. If you change too many things at once, you’re more likely to get overworked and take longer to recover. So progressive overload is just that: making progressive changes to continue getting stimulating sets and reps. Circling back to the boring repetitive programs, we can always add more and play with the different variables to ensure maximum effectiveness as we include variability. I love this passage from an article in Stronger by Science: More is More • Stronger by Science If you want to get stronger, the best thing you can do is train more, provided you’re sleeping enough, managing stress, and have good technique. Sure, other factors certainly matter. And sure, it’s certainly possible (though unlikely) to overtrain. But in the simplest terms possible, your current program is probably less effective than it would be if you just added an extra couple of sets to each exercise. If you’re not making progress, your default thought shouldn’t simply be, “time to find an exciting new program!” It should be either “time to add more work to my current program” or time to seek out a new program that employs more volume than my current one.” Rest and Recovery

If you’ve followed the How Much and Making Progress sections, then, I bet you can find the answer yourself to this last question: How often do I train and how much recovery time do I need? And yes. Of course: it’s all relative 😊 The answer we all love and hate. But that is real life for most of us. We know that, ideally, we would do 2 to 3 sessions a week of strength training per se. That leaves at least 4 days in the week to rest and recover. So, we may have 1 or 2 days in between each strength training session. Now, when it comes to rest and recovery, we have more than one option on what to do or not to do. Maybe you hear rest is for the weak. Or No pain, no gain. Or even a rest day is a lost day From my experience, it is quite the contrary.

Before we go on, a personal story: Last week, I spent a full week weighting myself every day (you don’t have to, I do it because I love data), and every day it was the same: not a single gram lost. I knew I was training properly following my program. I had gone a bit off track with my nutrition but not as much as not to see any progress at all. It was one day, and the rest of my week was on point. And then, Friday night came. I went to bed at around 11 pm. Woke up on Saturday at 9.30 am (a very rare thing for me, as I usually wake up at 7ish in the morning). Did my toilette routine and stepped onto the scale: I had “lost” 1 kilo. The moral of the story: the weight reflected the previous week was not real. It was a product of bloating and stress, plus some extra food. One good night’s rest set me back on track. Back to you. Progress towards your goal and having a healthier lifestyle include Recovery and Rest. These are crucial to seeing gains, physical and emotional. When it comes to organizing your training, you can decide to give yourself a full break from exercise in between the strength training sessions. Or you can choose to do a cardio session that day: run, jog, brisk walk, swim, bike, or dance. Whatever you prefer. Anything that elevates your heart rate, and you can keep up for 30 to 60 minutes. You can also choose to do some active recovery, like gentle stretching, some soft yoga, or having a massage or spa day. So, a training week could look something like this (just one idea) Day 1: Strength Training at the gym. Full Body Day 2: Salsa Class Day 3: Simply rest (from purposeful physical activity) Day 4: Strength Training at the gym. Full Body Day 5: Yoga Day 6: Brisk walk for 45 minutes Day 7: Full Rest When we consider getting healthier and developing healthy habits, we tend to focus on food and exercise first. And that is great. They are both important factors for our overall health and aging. But we must remember that sleep and rest are key components. If we don’t recover properly, we will have a harder time seeing results. Plus, when we don’t sleep well, we tend to eat more, move less, and be overall more stressed. This will affect our mental health and, thus, our physical health. As women, we often dread and fear the coming of menopause. It’s usually presented to us as this turning point when we can no longer do the things we used to do. Everything gets messy, painful, and uncomfortable.

We tend to see menopause as this stage in our lives that we must avoid. But can we really do so? Most likely, and from the current evidence and research, no. We cannot skip this part of our experience. So, if we have to go through it, how can we make it better? How can we take care of ourselves and give ourselves what we need to manage our expectations and experiences during menopause? We’ve discussed in previous articles what are the recommendations for exercise while pregnant.

But, what happens once the baby is born? Can we go back to exercise? And when? What type of exercise can we do? How do we know if we are on the right track? Do you remember a time when playing outside, going to the pool, and hanging upside down was pure joy, no matter the time of the month?

As women, why do we stop being so carefree in terms of movement and worrying so much about what we should and should not do once we start getting our periods? Contrary to popular belief, strength training can and should be done during pregnancy.

Ideally, we would have already been doing some form of strength training before getting pregnant and we can continue it during the pregnancy and after. But if that’s not the case, it is possible to start doing this at this stage of your life. Strength training helps maintain strength and aerobic fitness, as well as reduce risks of prenatal issues, such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and incontinence. And when paired with pelvic health physiotherapy, training during pregnancy can help reduce the risk and severity of several post-pregnancy health conditions. |